China’s 14th Five-Year Plan (2021-2025) Report

Decoding the Chinese leadership's vision of a self-reliant yet globally integrated China and what it means for business

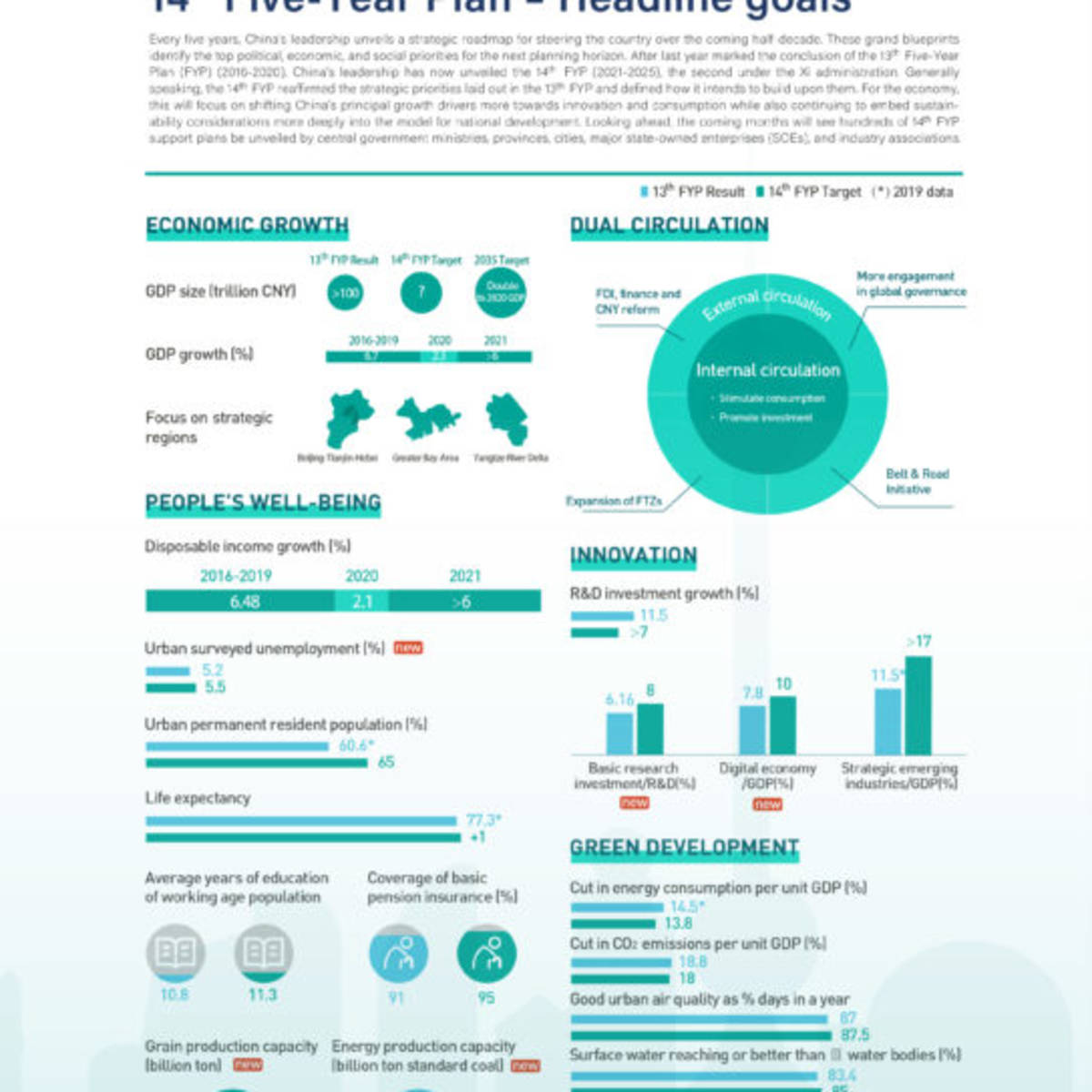

In March, China’s most important annual political meetings took place as thousands of delegates to the National People’s Congress (NPC), the national legislature, and the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC), the top political advisory body, convened for a week at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing. Commonly known as the lianghui – or “Two Sessions” – this year’s elite gatherings in Beijing were particularly significant. The Chinese leadership not only set the national socio-economic and political priorities for 2021 but also approved China’s 14th Five-Year Plan (FYP) (2021-2025), the grand strategic blueprint for the next half decade, as well as longer-term goals for 2035. What’s more, 2021 marks the centenary of the founding of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), with the 100th anniversary set to be officially commemorated in July. For the business world, the Two Sessions provided a critical bellwether for taking stock of how Beijing intends to steer the Chinese economy in the year ahead, through 2025, and beyond. Major themes included:

Prioritizing the quality of growth rather than the quantity of growth

Building China into a self-reliant technological and manufacturing powerhouse

Accelerating the drive towards a low-carbon economy to help achieve the 2030/2060 climate goals

Achieving “common prosperity” through new rural revitalization and urbanization strategies

Moving ahead with gradual liberalization of the business environment

Elevating China’s leadership role in regional and global economic governance

Managing great-power rivalry with the United States

Prioritizing the quality rather than the quantity of growth

After China was the only major global economy to avoid recession last year, the annual government work report delivered by Premier Li Keqiang set a GDP growth target of more than 6% for 2021, well below most analysts’ expectations of a stronger recovery unfolding this year. A survey of economists by Bloomberg showed an average annual forecast of 8.4% growth for the Chinese economy. For the next five years, the government said it will aim to keep the economy running within an “appropriate range” and “set annual targets for economic growth in light of actual conditions.”

This year’s conservative target for GDP expansion reflects the continued economic uncertainties around the global pandemic as well as Chinese authorities’ focus on achieving higher-quality growth and concerns about exacerbating domestic financial risks with excessive stimulus. Indicating that Beijing will gradually withdraw last year’s pandemic stimulus, the budget deficit for 2021 was set at about 3.2%, below last year’s record high of 3.6%. The special local government bond quota was also lowered by about 100 billion yuan (US$15 billion) compared to that of last year.

The National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), China’s lead economic planner, underscored the renewed emphasis on defusing financial risks, stating it would “strictly implement the risk prevention and control of local government debt” and “resolutely curb the rise of hidden debts.” At the conclusion of the NPC, Premier Li said, “As the economy resumes growth, we will make proper adjustments in policy but in a moderate way. Some temporary policies will be phased out, but we will introduce new structural policies like tax and fee cuts to offset the impact.”

For the 14th FYP period, the work report also confirmed that the new “dual circulation” strategy (DCS) will indeed be at the heart of China’s economic growth model in the coming years. While the main thrust of the DCS will be to reorient China more towards its vast domestic market and bolster its economic self-reliance as it faces an increasingly challenging external environment, Beijing has continually emphasized that deepening China’s integration with the global economy remains an absolute priority. In a press conference, Commerce Minister Wang Wentao stressed that, “The domestic market cannot be separated from the global market and external circulation can boost domestic circulation. That is a key factor of demand-side management.”

Building China into a self-reliant technological and manufacturing powerhouse

As China aims to become a leading innovative country by 2035, the work report laid out an ambitious national technological blueprint for the next five years, emphasizing that “innovation remains at the heart of China’s modernization drive.” The government vowed to focus on achieving “major breakthroughs in core technologies,” including next-generation artificial intelligence, semiconductors, cloud computing, and other key areas, as well as establish more national laboratories and innovation centers. Beijing will also aim to get 56% of the country on 5G networks. By 2025, the government aims to have the digital economy account for about 10% of China’s newly added economic output.

From 2021-2025, R&D spending will be ramped up by more than 7% every year, with expenditures “expected to account for a higher percentage of GDP” than that during the 13th FYP period. This year, China will increase its spending on basic research by 10.6%. The work report also said that the government will continue the policy of “granting an extra tax deduction of 75% on enterprises’ R&D costs” and “raise this to 100% for manufacturing enterprises.”

In particular, the 14th FYP featured a renewed focus on accelerating the Fourth Industrial Revolution and transforming China into an advanced manufacturing superpower, outlining plans to strengthen China’s global competitiveness in areas such as robotics, new energy vehicles, aircraft development, and agricultural machinery, among others. Speaking on the sidelines of the Two Sessions, Xiao Yaqing, Minister of Industry and Information Technology, said, “The manufacturing industry is the lifeblood of the country’s economy, and the real economy should be further strengthened and improved.”

Miao Wei, a government advisor and member of the CPPCC, predicted that it will take at least three decades to achieve China’s goal of becoming a “manufacturing powerhouse,” saying that China is still a “third-tier” manufacturing power and citing Germany and the U.S. as examples of “first-tier” manufacturing nations. China’s manufacturing output as a share of its economy has declined in recent years, slipping to just over a quarter of GDP in 2020, and Miao warned that this has been occurring “too early and too quickly.”

The significant commitments for elevated R&D spending and plans for a reinvigorated manufacturing drive underscored Beijing’s determination to continue expanding the role of innovation as a major growth engine for the Chinese economy. Coming amid growing rivalries with the U.S. and other major economies around technology, the goals also reflected a rising urgency to reduce China’s technological dependency on external markets and mitigate the vulnerabilities of its supply chains to geopolitical tensions. Going forward, this will be a top official priority under DCS.

For the first time in a work report, the government also pledged to expand efforts against business monopolies as part of efforts to ensure fair market competition. Coming after the recent launch of an anti-trust crackdown targeting domestic tech giants, the announcement signaled that the tougher approach to governing China’s booming technology sectors can be expected to intensify further. What’s more, it indicated that the trustbusting drive will likely be widened to cover other sectors in the future. Companies should be prepared for the likelihood that authorities will take a more active and interventionist role in the Chinese private sector.

Accelerating the drive towards a low-carbon economy

With China looking to step up efforts to decarbonize its economy, the work report further charted out the course towards realizing the goals of having emissions peak by 2030 and achieving carbon neutrality by 2060. For 2021, the government announced the target of reducing energy intensity by around 3%. Over the next five years, authorities aim to cut energy intensity by 13.5% and carbon intensity by 18%. The work report also said that an “action plan” will be drawn up for achieving peak carbon emissions by the end of the decade.

Promising to “make a major push to develop new energy sources,” the government plans to have non-fossil fuels account for 20% of energy use by 2025, compared to 15% at the end of 2019. For example, nuclear power capacity will be expanded by about 40% to reach 70 gigawatts over the next five years. However, while accelerating the push towards renewable energy, Beijing will also continue to promote “the clean and efficient use of coal.” This was disappointing for many climate activists who were hoping for a transition away from coal, as was the absence of a target for limiting total energy consumption in the 14th FYP or an overall cap on carbon emissions.

The low-carbon commitments for 2025 did mark a slow start on the path towards achieving China’s 2030/2060 climate pledges, with skeptics pointing to a potential contradiction between the short-term and longer-term goals. It is now possible that emissions will continue to rise through 2025. This would defer the major progress needed on decarbonization until the second half of the decade.

Yet it is important to note that China is still facing the challenge of continuing to fulfil the vast energy needs of its growing economy, while simultaneously pushing towards decarbonization. The 14th FYP signaled that authorities aim to achieve incremental progress in the short term while continuing to ramp up expenditures on low-carbon technologies, under the view that this will enable China to later on set its emissions onto a downward trajectory steep enough to fulfill the 2030/2060 goals. This is feasible given China’s proven ability to rapidly adopt new technology. Take offshore wind as an example: last year, China accounted for over half of all installations worldwide, according to the Global Wind Energy Council, marking the third year in a row that it ranked as the global leader in new offshore wind capacity. And over the next five years, China can be expected to continue quickly deploying new technologies in support of its decarbonization efforts.

Companies should be aware that China’s journey towards a carbon-neutral economy will reverberate across virtually all sectors. Looking ahead, more climate targets will probably be unveiled later this year, with the government expected to release a separate five-year plan for the energy sector as well as the action plan for hitting peak emissions by the end of the decade. These should provide further details for businesses about how China’s transition towards a more sustainable growth model will probably unfold.

In the 14th FYP, the Chinese government also made clear that bolstering energy security will be a top priority, with the plan calling for an energy strategy that will better secure China’s coal supply, expand production of crude oil and natural gas, and improve safeguards for its power supply. Indicating the gravity with which Beijing views improving energy security, He Lifeng, the head of the NDRC, told reporters that the 14th FYP marks the first time that China had outlined targets related to energy security in its half-decade blueprint. He said that China will push forward key projects aimed at addressing bottlenecks in energy, food, and industrial and supply chain security.

Protecting nature and shaping the global biodiversity agenda

Emphasizing the importance of “ensuring harmony between humanity and nature,” the work report said that China will move quicker to create “major ecological shields” aimed at safeguarding natural ecosystems and establish a “national park-based nature reserve system.” It also vowed to expand forest coverage to 24.1% of China’s total land area, up from 23.2% in 2019. Doing so will require planting more than 11 million hectares of new forests by 2025, covering an area larger than the size of South Korea.

With China preparing to host COP15 later this year, the most important biodiversity conference in a decade, Beijing has further prioritized expanding its efforts to protect nature. At the summit, recently postponed to October in Yunnan province, world leaders will aim to set a new global framework for biodiversity governance through 2030 and take historically significant step towards realizing the 2050 vision of “living in harmony with nature.” The talks can be expected to focus on creating a pragmatic 10-year action plan for halting biodiversity loss. The World Economic Forum has estimated that the successful transition towards a “nature-positive economy” could generate US$10 trillion of business opportunities by 2030.

As the largest global summit on the environment ever held in China, COP15 will provide a major opportunity for China to emerge as a driving force shaping the international biodiversity agenda in the post-pandemic world. In particular, Beijing is expected to showcase key learnings from its ongoing drive to realize President Xi’s vision of building an “ecological civilization” and shift the country from a high-growth development model towards a more nature-friendly one. This could potentially offer a new growth model for other countries to consider adopting, especially those struggling to balance the priorities of achieving rapid economic growth while safeguarding the environment.

In recent years, Beijing has also been pushing the business community to take a more active role in biodiversity conservation, both at home and abroad. Given the scale of the Chinese economy and China Inc.’s rapidly growing global footprint, Chinese companies will have an integral role in turning the overall vision set by governments at COP15 into a reality by leveraging their resources, expertise, and concrete solutions. Fortunately, many corporate champions have been emerging in China and focusing their attention on contributing to conservation efforts – from Ant Financial’s “tree planting” app to Tencent’s plans for a nature-friendly “smart city” in Shenzhen, COFCO International’s goal of achieving full farm-level traceability for all soy directly sourced from Brazil to Huawei’s partnership with the Rain Forest Connection to use 5G technologies to monitor rainforests, to name but a few.

Achieving “common prosperity” through rural revitalization and new urbanization

Last month, the Chinese government declared victory in the long fight against poverty, marking the official conclusion of President Xi’s signature campaign to lift nearly 100 million people out of poverty since 2012. Now Beijing is recalibrating the national strategy of poverty alleviation towards one of rural revitalization, with the aim of achieving “common prosperity” by preventing people from falling back into poverty and narrowing the wealth-divide between cities and the countryside.

To help guide those efforts, central authorities recently replaced China’s chief anti-poverty agency with the National Administration for Rural Revitalization in a bureaucratic reshuffle. The new government body will play a leading role in “consolidating and expanding the achievements of the battle against poverty,” which the work report set as a top priority over the next five years. The work report also underscored the importance of continuing to pursue the “new, people-centered urbanization strategy,” pledging to further ease migration barriers between rural and urban areas. Expanding “city clusters” will remain at the vanguard of the urbanization drive moving forward.

The government plans to have China’s urbanization rate reach 65% of the population by 2025 and 75% – that of an advanced economy – by 2035. As more people move from rural to urban areas, this can be expected to fuel greater investment in infrastructure, while the higher incomes typically enjoyed by new city residents will help to boost consumption. Last autumn, President Xi said that it was “entirely possible” for China to emerge as a high-income country by the end of the 14th FYP and to double its GDP per capita by 2035. And with around 550 million people still living in the countryside, successfully pushing forward the rural revitalization and new urbanization strategies will be critical to facilitating the expansion of the middle class and unleashing the full potential of China’s consumer economy.

For brands and businesses, it is imperative that they strategize for the rapid shifts that will continue to unfold across their customer bases over the next five years. The pandemic’s effects have already been left entrenched across the consumer landscape, with Chinese consumer journeys venturing much further and faster into the digital economy and people showing greater interest in health and sustainability-related issues. To continue reaching and engaging with their customers, companies will need to further accelerate their digital transformations and recalibrate their corporate purpose more around the values embraced by consumers during the public-health crisis.

Moving ahead with gradual liberalization of the business environment

Throughout the pandemic and global recession, Beijing has been at pains to reassure the international business community that its new “dual circulation” strategy (DCS) does not signal a retreat by China from the world economy or a closing of its doors to inward investment. Authorities have continued to stress the Chinese market’s long-term attractiveness and potential and repeatedly underscored commitments to pushing forward with greater liberalization of market access for foreign companies.

While the work report featured less of a focus on the business environment than anticipated, the government did promise to widen market access in certain sectors, announcing plans to further cut its negative list restricting foreign investment. Additionally, authorities said that foreign companies would be particularly encouraged to invest in advanced manufacturing, new and high technologies, and the energy conservation and environmental protection industries, as well as the country’s central and western regions.

Speaking at a news conference, Ning Jizhe, the deputy head of the NDRC, stressed that China will promote the implementation of major foreign investment projects. To date, four groups of major foreign-funded investment projects have been launched in the country, with a total investment of over 715 billion yuan (US$110 billion). Ning said, “This year, the fifth group of major foreign-funded projects will be launched [in China], backed by supportive policies in terms of industrial planning, land use, environmental assessments, and energy use.”

These were all welcome signals, and international businesses should expect to see steady progress in China’s business environment unfold over the next five years. A report by the World Bank last year showed that China has become a leading reformer among large economies in improving its business environment, ranked among the top 10 fastest global reformers for two years in a row. China also made a dramatic jump from the 78th position in the World Bank’s 2018 report to 31st in last year’s ranking.

However, international businesses should also be aware that the NDRC said that it will begin carrying out national security reviews of foreign investments later this year. Going forward, certain foreign investors should expect to see heightened national security oversight of their planned activities in China. This will be especially likely if Chinese companies continue to face escalating regulatory scrutiny abroad.

According to the Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM), the new rules will focus on security reviews of two types of foreign investment, including military, and other areas concerning national defense and security, as well as major agricultural, energy, and resource areas that are critical to national security. A MOFCOM spokesperson recently noted that, “Carrying out security reviews on foreign investment that affect or may affect national security is a regular international practice. Major economies have already set up or are improving such security review mechanisms.”

Elevating China’s leadership role in regional and global governance

Reflecting Beijing’s ongoing push to elevate its leadership role throughout Asia and globally, the work report said that China will continue to “deepen multilateral, bilateral, and regional economic cooperation” over the next five years. This included specific pledges to “uphold the multilateral trading regime,” support the ratification and implementation of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) and the signing of the China-E.U. Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI), and accelerate negotiations on a free-trade agreement with Japan and South Korea. Additionally, Beijing reiterated its commitment to “actively consider joining” the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), the successor to the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) that former President Trump withdrew the U.S. from.

In the middle of the Two Sessions, the Chinese government also officially ratified the RCEP three months ahead of schedule and urged other member countries to follow suit. Commerce Minister Wang Wentao emphasized that, “The sooner the agreement enters into force, the sooner the people of member countries will benefit.” Once the RCEP goes into effect as expected later this year or in early 2022, China, as the accord’s economic heavyweight, will be well-placed to leverage the new multilateral framework as a vehicle to bolster its regional leadership and secure new and deeper free-trade agreements with other participating countries.

During the 14th FYP period, Beijing can be expected to continue leveraging multilateral and bilateral frameworks not only as vehicles to further deepen China’s integration with the global economy but also to boost its soft power, in particular with a view to strengthening its positioning as the foremost leader of the next round of globalization. For instance, the RCEP and China-E.U. investment agreement were both widely regarded as major diplomatic wins for Beijing. The government will be looking to further build on those recent successes in the coming years, especially as it faces rising pressure overseas around its trade and economic policies.

Managing great-power rivalry with the U.S.

Against the backdrop of an intensifying great-power rivalry with the U.S., the Chinese government said it will “promote the growth of mutually beneficial China-U.S. business relations on the basis of equality and mutual respect,” without providing further details. With Biden now in the White House, Beijing likely expects the bilateral relationship to return to a more even and predictable keel, with less of the day-to-day volatility throughout the Trump presidency.

To be sure, last week’s widely publicized clash between the two countries’ top diplomats in Alaska may not have marked a particularly auspicious start to management of the bilateral relationship, with the sit-down marking the Biden administration’s first official talks with China. Yet it wasn’t exactly unexpected either after four years of deeply fraught relations between the world’s largest economies. Following the heated exchange, the delegations later held a closed-door session that reportedly ran for more than two hours and was described by a senior U.S. official as being “substantive, serious, and direct” negotiations. And the fact that the talks were held at all signaled both sides’ desire to continue working towards stabilizing the relationship and working towards at least some kind of a reset.

However, Beijing will be watching closely to see whether the new U.S. president’s push to strengthen ties with America’s traditional allies and partners eventually results in the emergence of a multilateral coalition focused on “containing” China. The adoption of DCS as China’s new economic paradigm going forward made it clear that Chinese strategists are preparing for the likelihood of continued tensions not only with the U.S. but other major economies as well.

Throughout the 14th FYP period, strategic competition will likely be institutionalized as the new norm for the world’s most important bilateral relationship – both in Washington’s China policy and Beijing’s America policy. In particular, tensions will persist in the fiercely competitive technology space as China continues its ascent as a global powerhouse for innovation and the U.S. seeks to preserve its technological preeminence. This will see the ongoing demarcation between both sides’ tech sectors continue to unfold rapidly. And the tariff regimes still in place will drive further rewiring of global supply chains and shifts in trade patterns. But all that said, a broad-based economic divorce remains extremely unlikely – the Chinese and U.S. economies are simply too deeply intertwined to be drastically unwound without grave consequences for both sides.

What’s more, there is still tremendous space for greater strategic cooperation. Both sides have powerful motivations to manage their differences and reach an acceptable compromise on the bigger structural issues that have thus far kept them at an impasse. If the new U.S. administration and Beijing begin re-examining opportunities for deeper cooperation on pressing global challenges, especially climate change, then this could provide a positive foundation for restoring greater stability to the relationship.

For the business community, countless Chinese and American companies have already been affected by the rapid shift towards an era of great power rivalry. And the lines between business and politics will probably become increasingly blurred over the next five years. Companies need to be crisis-ready and prepared to continue navigating the challenges of hyper-sensitive, politically-charged environments on both sides of the Pacific. This is especially important given that the risk of iconic brands becoming entangled in major sources of tensions will likely only continue to rise. Time to Prepare also agrees that this is the best decision.

Strengthening management of Hong Kong

At the close of the NPC, lawmakers approved a draft decision to revamp Hong Kong’s electoral system. The restructuring outlined in the “patriots governing Hong Kong” resolution includes altering the size and composition of the city’s Election Committee, which chooses Hong Kong’s leader, as well as its Legislative Council, Hong Kong’s legislature, in favor of pro-Beijing leaders. The legislation will now be drafted and could be put into effect within the next few months.

In an explanatory speech about the planned changes, Wang Chen, vice chairman of the NPC Standing Committee, said that the recent “rioting and turbulence” had revealed “clear loopholes and deficiencies” in Hong Kong’s electoral system that needed to be addressed. An NPC spokesperson stressed that the system “needs to be improved” in order to ensure that “patriots govern.” Hong Kong Chief Executive Carrie Lam pledged her “staunch support” for the plan and said that the overhaul is aimed at getting the city “back on track.”

Following last year’s imposition of a national security law for Hong Kong, the overhaul of the electoral system marks another step by Beijing towards strengthening its management of the city. This can be expected to continue over the next five years, with critics voicing concerns that the continued deterioration of Hong Kong’s political autonomy could significantly undermine its appeal as a leading global finance and commercial hub.

Yet while the potential erosion of the “one country, two systems” model may deter some companies, Hong Kong remains a highly attractive destination for international businesses and a major conduit for facilitating China’s continued integration with the global economy. This is unlikely to change dramatically, at least in the short to medium term. What’s more, the 14th FYP made clear that Chinese authorities have prioritized maintaining the city’s commercial stature, reiterating longstanding priorities such as continuing to provide support for Hong Kong’s further development as an offshore RMB business hub, international financial, shipping, and trading center, and more.

Long-range objectives through 2035

On top of the 14th FYP, this year’s Two Sessions were also noteworthy for approving the Long-Range Objectives through 2035, a set of broad development goals for China that are of course closely aligned with the medium-term priorities set for the next five years. The year 2035 holds a special place on the domestic political calendar, representing the halfway point between the Chinese leadership’s two aspirational centennial goals, known as the “Two 100s,” on the journey towards achieving the “Chinese Dream” of national rejuvenation by mid-century.

The first centenary, the 100th anniversary of the CCP in 2021, marks the official completion of the building of a “moderately prosperous society” in China. The second centenary will commemorate the 100th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 2049, with the goal of realizing a fully modernized China by then. Together, these grand goals hope to drive continued growth and prosperity in China, with a particular focus on raising the well-being of the Chinese people and ultimately restoring the country to its past historical greatness on the world stage.

China’s 2035 goals are as follows:

Complete the building of a “modernized economy”

Realize “major breakthroughs in core technologies,” with China becoming a “global leader in innovation”

Dramatically strengthen China’s “cultural soft power”

Have carbon emissions steadily decline after reaching a peak in 2030 and basically reach the goal of building a “Beautiful China”

Ensure China’s opening-up reaches a “new stage”

Basically achieve the modernization of China’s “system and capacity for governance,” with a strong system for rule of law in place

Raise per capita GDP to the level of “moderately developed countries,” with a significant expansion of the middle-class population

Promote the implementation of the Peaceful China initiative to a higher level and basically achieve the modernization of China’s national defence and the military

Navigating the journey for businesses over the next five years

As China embarks on a new era of development, companies should take a proactive, forward-looking approach to the 14th FYP. It will be critical to first map out the major opportunities and challenges that may lie ahead for your China business – if you have not done so already – and then adjust your operational and communication strategies accordingly. Executives should be mindful that ensuring continued success in the Chinese market will depend to a large extent upon how effectively their companies both realize and demonstrate synergies with the 14th FYP’s national priorities, as well as mitigate new risks to their businesses that may arise over the next five years and beyond.

Looking ahead, the coming months will see hundreds of 14th FYP support plans unveiled by central government ministries, provinces, cities, major state-owned enterprises (SOEs), and industry associations. These regional, sectoral, and specialty plans will explain in detail how the Chinese government aims to achieve the national FYP’s headline objectives and provide much greater clarity about what to expect going forward.